By Phillip Payne with Brian Moritz

Doomed to repeat it, or just rhyme?

History is a tricky subject.

History is not just in our classrooms, museums, and libraries but it is all around us on our TVs, newsfeeds, and in the all-consuming politics of our culture wars.

Americans have taken heed of George Santanyana’s warning that “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it” and Mark Twain’s “History doesn’t repeat itself, but it does rhyme”(which, maybe, appropriately Twain might not have actually said) Americans pay attention to history. They have flocked to history in search of understanding the rhythm of our lives, even as history’s place in our educational landscape is increasingly precarious thanks to declining enrollments and the ravages of the history wars.

Indeed, there is a cottage industry of writers and podcasters dedicated to revealing what your history teacher hid from you. Writing about historical podcasts, a popular genre, Jason Steinhauer notes that “entire shows are built around the conceit that events from history have been forgotten, omitted or deliberately concealed.” These podcasts offer “a relief from professional history—or a relief from the perception of professional history—remains a hallmark of e-history across platforms and formats.” 1

These quotes from Santayana and Twain, and a lot of our online history, assume that we use history for its predictive qualities and thus risk searching for a history to justify positions taken in the present. Without a doubt, the nuance and context that the study of history provides helps in understanding the present moment, but when debating the role of history in contemporary life, the issues of presentism and relativism always appear. Historians have always offered commentary on current events, often in the form of context and background. In the classroom context, it can be almost impossible not to bring in relevance to the present moment as one searches for ways to connect with students, making a lesson valuable to them as citizens.

The past decade saw historians rising in public prominence by offering insight into current affairs, often becoming combatants in partisan culture wars. Nicole Hannah-Jones’s 1619 Project with the New York Times Magazine, for which she won a Pulitzer Prize in 2020, centered United States history around the African-American experience. The 1619 Project became a flash point in discussion of race during the Black Lives Matter movement. Heather Cox Richardson’s “Letter from an American” newsletter placed current political events into historical context. Timothy Snyder’s On Tyranny: Lessons from the Twentieth Century became a bestseller as Americans looked to understand fascism and authoritarian movements in light of authoritarian populists movements around the world. Princeton historian Kevin Kruse achieved celebrity in large part thanks to his Twitter account. Recently he edited, with Julian E. Zelizer, Myth America: Historians Take on the Biggest Lies and Legends about Our Past, in which historians debunk bad history, as described on the book’s website, with a distinct ideological purpose: “The United States is in the grip of a crisis of bad history. Distortions of the past promoted in the conservative media have led large numbers of Americans to believe in fictions over facts, making constructive dialogue impossible and imperiling our democracy.”

This tendency has seemingly exploded fueled by the intensity of our culture-wars-infused politics, the rise of social media, and the desire among academic historians to make the case for their discipline. Historians fulfill the role, as often happens in the classroom, of providing context and patterns. However, as Jason Steinhauer and others have noted, the incentives of the social web can be very different from the incentives of the museum or classroom. The history classroom can, and should be, a place to learn context but also a safe place where people can discuss the issues at hand. This can be a far-cry from the debates raging on Facebook, X or other platforms.

While there is a great deal of value in historians and journalists collaborating and borrowing, there can be pitfalls. The rise of historians as pundits created a concern in the academy around the issue of presentism. Is the study of the past a thing unto itself or something that only exists to illuminate the here and now?

The First Draft of History

The old adage that journalism is the first draft of history is another saying that is worth thinking about. Historians, depending on the research area, often rely on contemporary journalism in recreating the past, hence the idea that journalism is the first draft of history. Particularly for historians writing about the past few centuries, what was reported in newspapers has a significant impact on the history that gets told.

Historians and journalists share some common traits. Among these would be a commitment to research and accuracy, quality writing, analysis and narrative, explaining complicated subjects, and working with the public. It is also relatively common for journalists to write popular history. There has always existed tension between popular historians who write for mass audiences and academic historians who write for other scholars. Scholars argue that popular historians write simple narratives to reach the widest audience while academic historians are critiqued for writing narrow and dense prose. However, the internet, especially web 2.0 and social media, has blurred these lines.

While historians and journalists share many traits, there are differences. Journalists reach a larger audience and function under tighter deadlines than is typical of academic research and publishing. By definition, journalists are guided by the news and as such explain the here and the now in ways that a larger audience can find engaging and understandable. The internet deeply disrupted journalism just as it appears to be disrupting history now, but merging the fast pace of journalism with the slow discipline of history is not without its difficulties.

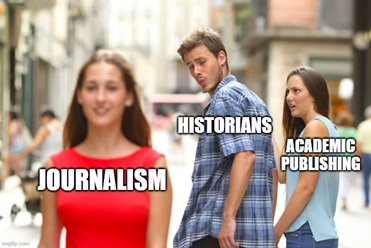

The relationship between history and journalism is a little like that meme of the boyfriend looking at another woman. Academic historians are often criticized for not speaking to larger audiences, and trends within education reinforce the need to make history relevant. A typical scholarly book or journal article can take years to research and write with an intended audience of fellow scholars in the field. This means that a scholarly monograph (a fancy word for a scholarly work) will sell hundreds, maybe thousands, of copies or less. Many of the books and journals will go into academic libraries, either digitally or physically, waiting to be checked out by scholars and students.

Publishing academic history is not a money making proposition nor is it intended to be. Historians are notorious for inaccessible writing that is not suitable for wider audiences. Historians writing for other academics make complex arguments with complex language that sounds like jargon to the uninitiated (see our use of “monograph” above). However, scholarly debate is intended to further our understanding of the past and that should make its way into textbooks and classrooms.

Is the Past a Foreign Country?

One concern is that a focus on current events distorts the work of history in several ways. Among academic historians, the conventional approach to scholarship is driven by historiography and archives. What does this mean? When an historian sits down to decide upon a new research topic, the historian asks questions. Historiography is the inside-baseball term for the body of literature around a given topic and the writing on the hows and whys of practicing history – how one should evaluate evidence, form an argument, and understand the philosophy of historical inquiry.

For example, when starting a new research project our historian might look at what has been written on a topic, say the Great Depression, and then ask what gaps exist in the literature (referred to as secondary sources) or where does one disagree? What are the debates in the field? In other words, historians often start with question(s) informed by what other historians have written.

Having reviewed the literature of the existing scholarship (aka the secondary literature), mapped out the debates, and formed some questions, the academic historian’s next step is to see what resources exist to answer those questions. This usually means archival research. Historians might take into account other types of evidence such as material culture. Material culture is the study of the built world. An example of this might be looking at architecture or headstones in a cemetery for clues about the past.

This is a very different process than writing a newsletter or op-ed connecting history to current events.

“The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” William Faulkner

The cliche that journalism is the first draft of history papers over the complicated relationship between the two endeavors. In recent years, there has been an emphasis on “hybrid journalism,” here meaning the collaboration and overlap in the public discourse between history and journalism. Historical content has exploded on platforms such as podcasts, and newsletters (especially Medium and Substack) as journalists turned to history and historians turned to journalism, stepping “into the convulsion of the world” to quote from Robert Penn Warren in All the King’s Men.

History and journalism both suffer from an ease of entry that digital technology and the internet have only made easier. A survey of where Americans get historical information found that 62 percent get it from TV news with 55 percent using newspapers and magazines for historical knowledge. Nonfiction history books came in much lower on the list at 32 percent but above social media at 26 percent. College courses came in below video games and DNA tests, with 8 percent of the public citing courses as a source of historical knowledge.2 The Trump years also saw a bump in interest in political journalism, perhaps to the point of pushing out coverage of other news; it would appear that the bump in interest in history as political commentary rode that wave.

In Robert Penn Warren’s All the King’s Men (1946), the character Jack Burden observes the rise, and eventual demise, of Willie Stark the ambitious and corrupt governor of Louisiana who was probably (despite Warren’s denial) a fictional stand-in for Huey P. Long, aka the Kingfish and political boss of Louisiana during the 1930s. All the King’s Men is one of the great political novels in American history, exploring many themes including the tension in Burden’s character, who had been both an aspiring historian and a professional journalist, between observing and explaining or acting in the political sphere.

Burden had been an aspiring historian but having failed to finish graduate school he embarked on a career as a newspaperman before becoming a political operative for Stark. Burden is torn between observing or acting; should he “go into the convulsion of the world, out of history into history and the awful responsibility of Time.” (661) Warren’s fictional historian/journalist/politico faced a dilemma familiar to historians and journalists today.

* * *

Phillip Payne is chair of the Department of History at St. Bonaventure University. Brian Moritz is director of the online M.A. programs in sports journalism and digital journalism in St. Bonaventure’s Jandoli School of Communication.

Visit our Hybrid Journalism Page to learn more about the project and view other articles. To learn more about this article, click below to watch a conversation with the authors, hosted by Cassidey Kavathas.

Click here to learn more about our Hybrid Journalism Project.

Resources:

Steinhauer, History Disrupted: How Social Media and the World Wide Web have Changed the Past

Roy Rosenzweig and David Thelen, The Presence of the Past: Popular Use of History in American Life (1998)

Survey of Public Regarding History: Introduction | AHA

Where Do People Get Their History? | AHA. (this updates Rosenzweig and Thelen)

Playing to the Cameras | History News Network

Why Historians Should Use Twitter: An Interview with Katrina Gulliver | History News Network

Jonathan Zimmerman: Why—and How—I Write Op-eds

“Those Who Do Not Learn History Are Doomed To Repeat It.” Really? – Big Think

- Jason Steinhauer, History Disrupted: How Social Media and the World Wide Web have changed the Past (2022), 81 – 82. ↩︎

- Survey of Public Regarding History: Introduction | AHA ↩︎

Categories: hybrid journalism, Jandoli Institute, Media

Leave a comment